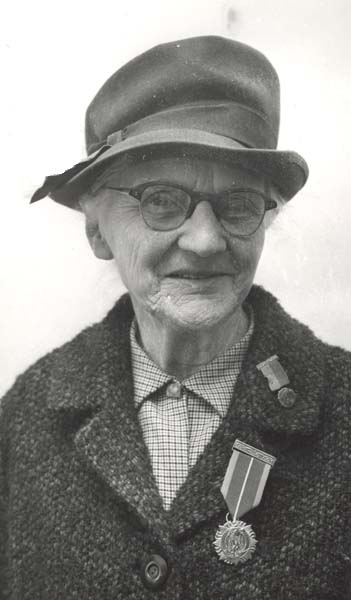

Maud Gonne MacBride

Gonne, an Irish patriot, actress, and feminist, presented herself as Ireland’s Joan of Arc (it was her nickname), and was an inspiration to many Irish women of her time. She was the founder of Inghinidhe na hÉireann (Daughters of Ireland), an organization that was later subsumed into Cumann na mBan.

The imagery surrounding Saint Joan of Arc was reinforced by Gonne’s fellow patriot and nationalist, Constance Markievicz, who invoked the Saint in an address to young Irish women in 1909 with,

’And if in your day the call should come for your body to arm, do not shirk that either. May this aspiration towards life and freedom among the women of Ireland bring forth a Joan of Arc to free our nation’ (Ward).

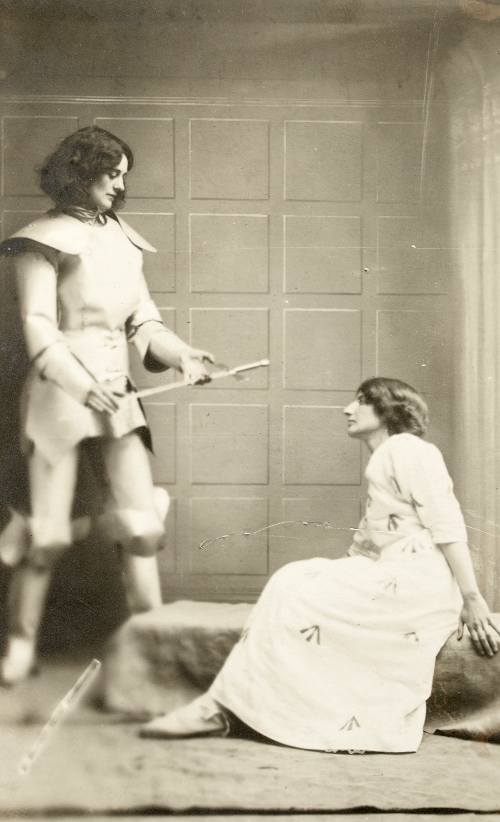

Markievicz, who trained as an artist, knew the importance of imagery and the power of visuals. Appearing in a pageant in 1914, dressed as Joan of Arc, she presents a woman political prisoner with a sword. Portraiture of her in the early 1900s presented her in military uniform, a call to Irish women to join her in taking up arms (Maguire).